In need of some planting tips for spring? Our homesteading guide will help you know what to plant now and what to plant later.

Planting Tips For Spring: Cold-Hardy, Heat-Seeking, and Seedlings

There is something special about raising your own food when you live in the north. Up here, growing vegetables amounts to a delightful amalgamation of art, science, and luck.

One of the most important points to consider when planting your garden is how to get them into the ground. It sounds simple, right? Dig a hole, pop in the seed, and done. In some cases it really is that easy, but there is a little more to it than that.

The way to plant vegetable seeds can be roughly divided into three basic categories: cold-hardy, heat-seeking, and seedlings. There are several types of vegetables which can yield success in more than one category, and a few which do not completely fit into any of them. I will say a few extra words about those particular varieties when we get to them.

Planting Cold-Hardy Plants In Spring

First we'll discuss the cold-hardy plants that go in as seeds. Many plants which can withstand cold are ones which cannot tolerate heat. A few can thrive in both ends of the spectrum, but a general rule of thumb is this: if it is possible to plant seeds in the cold, do it. Their optimum conditions might not last all summer, so get an early start; if plants are happy in 45 degrees, they might wither and bolt at 90.

Spinach is a good example of a plant that not only tolerates cold, but prefers it. Peas, Asian greens, and most lettuces are this way also. Get these seeds into the ground as soon as the soil is able to be worked, which in my growing zone is usually around April.

Other cold-hardy plants are carrots, beets, radishes, and chard. They can go into the ground fairly early in spring, and are able to tolerate the moderate heat that we get in my region. One of the beautiful aspects of plants that thrive in both ends of the temperature spectrum is that they can be “succession planted”. That means they can be planted continually every few weeks all summer, usually from April to August.

Some plants can tolerate heat only at certain stages of development. That means they might be happy as little baby plantlets in the summer heat, but not as adults. It sounds complicated, but it really can turn into a nice perk—plant these varieties in April for an early summer harvest, and again in late July for a fall harvest. Most of the cold-loving greens I told you about are conducive to dual harvests, as well as many brassicas.

Brassica is a genus that includes a wide variety of plants. Broccoli, cauliflower, and brussels sprouts are all brassicas, but so are kale, collard greens, cabbage, and kohlrabi. And alas, brassicas are one of those types that I warned you about—they fit into more than one planting category, yet do not fit quite perfectly.

The one thing brassicas all have in common is that they prefer cool and cloudy over hot and sunny, and do not even mind downright cold. Beyond that, however, they are all over the place. Kale and collards can be succession planted for baby greens, planted in spring for enormous plants by late summer, and planted in fall for food that can be harvested well into the winter months. Cabbages come in early varieties and late varieties. The latter take up an entire northern season and can be planted only once, while others afford a bit more flexibility. Brussels sprouts require a long growing season as well, as do many cauliflowers. Broccoli can mature in as little as two months or as much as four, and can be planted as seeds in the frigid spring ground or as seedlings much later.

I told you brassicas were complicated. But the good new is, they are as flexible as they are complex.

The cold-hardy takeaway is this: If your garden beds are ready and your soil is workable, go plant your spinach, lettuce, green peas, carrots, radishes, beets, chard, and kale right now. And if your other brassicas say on the seed packet directions that you can plant them as seeds in early spring in your zone, try that too.

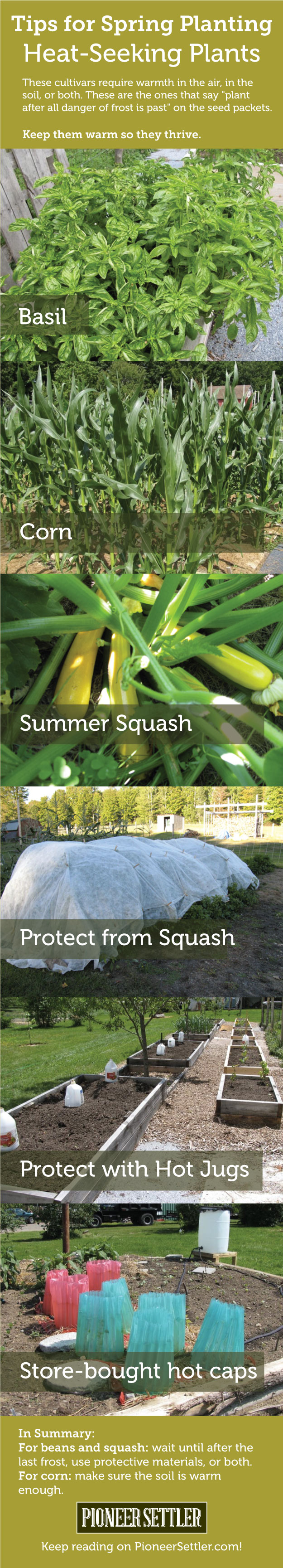

Planting Heat-Seeking Plants In Spring

The next category is vegetables that are heat-seeking. These cultivars require warmth in the air or in the soil or both. These are the ones that say “plant after all danger of frost is past” on the seed packets.

Vegetables such as beans and squash are prime examples of those which cannot tolerate frost. Many herbs like it warm, particularly basil. But how do you know if the last frost has occurred? You cannot always know beyond a shadow of a doubt. Traditional folk wisdom in my region says to plant after the full moon closest to Memorial Day. There are a lot of variables in there, but it makes a good jumping-off point. Modern-day gardeners have cutting-edge meteorological information at their fingertips, literally, and can use professional predications to help them identify the last frost.

But how do you know if the last frost has occurred? You cannot always know beyond a shadow of a doubt. Traditional folk wisdom in my region says to plant after the full moon closest to Memorial Day. There are a lot of variables in there, but it makes a good jumping-off point. Modern-day gardeners have cutting-edge meteorological information at their fingertips—literally—and can use professional predications to help them identify the last frost.

However, here is a little-known tip. Most seeds will not be damaged by frost—it is only the tiny plants which are vulnerable. If there does happen to be an unpredicted frost a few days after you plant beans or squash, you will probably be okay if they have not yet germinated and emerged from the soil.

And the best part is this: you can always cheat the weather a little bit. Or even a lot, depending upon how much effort you are willing to put into it. The bottom line here is that any coverings can help protect your delicate plants. Fabric row covers, plastic hoop houses, or even individual coverings made from recycled gallon milk containers can all be used to add a degree or two – just enough to make a crucial difference in the life of a tender young plant shoot.

Corn is the notable exception to these guidelines for heat-seeking plants. Corn needs to be planted in warm dry soil—typically 60 degrees—and is in danger of rotting in soils too cold or wet. It is wise to use a soil thermometer to make sure.

To recap the heat-loving plants directions: for beans and squash, wait until after the last frost, use protective materials, or both. For corn, make sure the soil is warm enough.

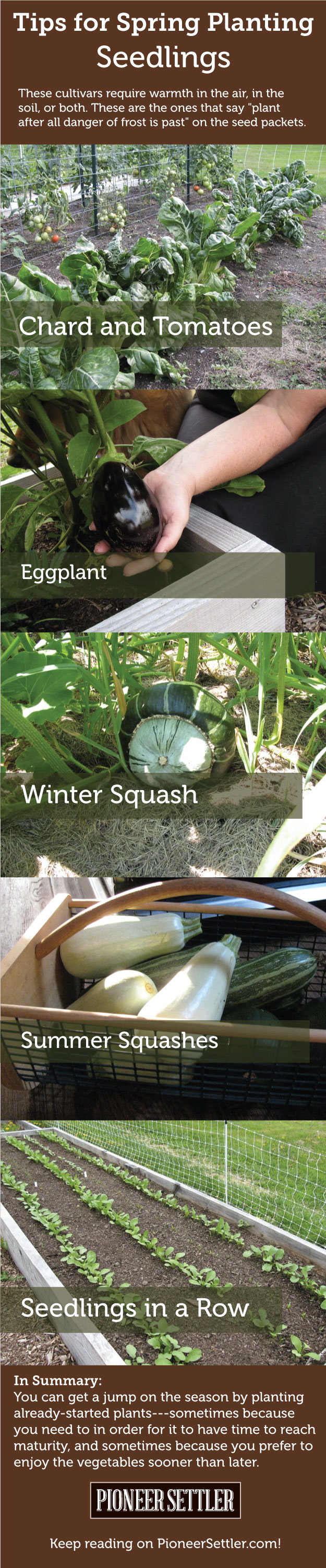

Planting Seedlings In Spring

Now for the third category: seedlings. These are plants that are planted indoors in a greenhouse and set into the outdoor garden once they have grown into tiny plants. Some beginners start their own seeds indoors, but it is probably easier to purchase them from a local garden nursery.

Repurpose a strawberry container to sprout your own seeds. Click for 32 more Seed Sprouti… https://t.co/gJtKhD5nBh pic.twitter.com/9XlZrKxpK0

— Homesteading (@HomesteadingUSA) April 2, 2016

The majority of the plants in this category are those which either have a long enough growing season that success is iffy in a northern climate, are very sensitive to cold, or are in such high demand on the menu that the gardener needs to get a head start.

No matter the reason, the garden vegetables usually planted as seedlings in northern climates include: tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, cucumber, melons, pumpkins, and celery.

And maybe brassicas. It is typical to plant all long-season brassica cultivars as seedlings, including cauliflower, brussels sprouts, some cabbages, and some broccolis. And squash. Here is another family of vegetables which doesn't quite fit into any one category. Squashes are subdivided into summer and winter varieties. Summer squash is quick-growing, does not store well once picked, and is eaten with skins on. Winter squash is generally slow-growing, keeps in root cellars for months, and is peeled before eating. Summer squash are usually direct seeded in warm ground, but some people like to start them ahead. If you are not sure, try it both ways. If they are both successful, you will have a very convenient span of time between the time the seedlings bear fruit and the direct-seeded plants bear, allowing you to catch your breath between bites of zucchini and crookneck squashes.

Winter squash offers a similar option, but the decision is determined more of length of growing season. A cultivar that needs 120 days to maturity may not do well in a zone which typically offers only 100 days between the last and first frosts. Those varieties would do best started indoors and planted as seedlings, but many varieties do just fine when direct-seeded.

In summary of seedlings, you can get a jump on the season by planting already-started plants—sometimes because you need to in order for it to have time to reach maturity, and sometimes because you prefer to enjoy the vegetables sooner than later.

Northern summers are short and intense, and offer special challenges and extraordinary rewards to vegetable gardeners. Go ahead, dig in. Plant some now, plant some later, and enjoy an entire season of enjoying the delicious fruits of your labors.

Are you more confident with your spring gardening? Let us know what you think below in the comments!

[…] 7. Planting Tips For Spring: Cold-Hardy, Heat-Seeking, and Seedlings […]